The air at Sicks' Stadium in Seattle on April 1, 1969, smelled of new wood, damp hope, and the uncertainty of a franchise taking its first breath. On the mound, a 31-year-old man, skin tanned by the Caribbean sun and Venezuelan winter winds, adjusted his Seattle Pilots cap. Diego Seguí, born in Holguín, Cuba, exiled in Mexico, forged in the American minor leagues, and sanctified in Latin American stadiums, was preparing his first pitch.

He wasn't a young prodigy; he was a survivor. And that afternoon, although the California Angels would defeat him 7-0, Seguí pitched something more than a ball: he pitched the first chapter of an elusive legend, a man whose baseball map was a worn atlas of crossed borders and displaced loyalties.

He always adapted to the conditions and the situation. When it seemed his slider could be predictable as a big weapon, he lowered the curtain to showcase a slippery and tangled forkball. My uncle Beto was a die-hard Seguí fan. Occasionally, he spoke to me about himself and Camilo Pascual. He didn't exactly tell me about Seguí's power. He let me know what it meant to graduate as a pitcher when all your power is entering a downward spiral. Every time I watch this video of Seguí, I'm reminded of that facet my uncle told me about: the art of deception at its finest. Experiencing the myth of reinventing yourself when your most youthful powers slip away with age.

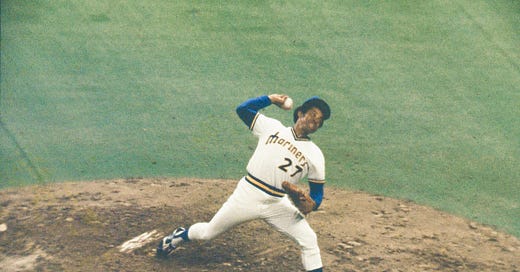

He was the perfect imperfection to inaugurate a team that would barely last a year. Eight years later, in the newly opened Kingdome, that same man, now with the seams of age straining his right arm, would emerge from the Seattle Mariners’ bullpen. The only player in history to wear the colors of both failed and reborn Seattle experiments. Diego Seguí, the nomad, always arrived just as something was starting.

Seguí wasn't the prototype of the Cuban ace who arrived in the Major Leagues with fanfare. Having fled Cuba after the Revolution in 1960, his route was circuitous: first to Mexico, where his powerful arm made him a star in the Mexican League, pitching all-nighters under flickering lights for teams like the Diablos Rojos. American scouts were wary: he was already 24, a veteran age for a rookie. But the Kansas City Athletics, eternal collectors of raw, discarded talent, saw something: the fastball that whistled like the wind slicing through a royal palm tree, and a curveball that fell like a wounded bird. He arrived in 1962, not as a phenomenon, but as a craftsman willing to work.

The Ace Up His Sleeve and the Home Run Off Bench

By 1970, with the Oakland A's, Seguí was no longer the workhorse. Age and accumulated innings had turned him into a cunning reliever, a master of deception. His secret weapon was no longer a speedy fastball, but a slider that slipped in like a thief in the night, viciously biting the outside plate. His moment of individual glory came in the All-Star Game in Cincinnati. He entered in the seventh inning, bases loaded, one out, the crowd roaring. At bat, Johnny Bench, the Reds' man-mountain, the terror of pitchers. The stadium awaited disaster. Seguí, with the calm of someone who has seen revolutions and teams disappear, took a deep breath. He threw a perfect slider, low and wide. Bench lunged, punched air. Strikeout! The roar turned into a murmur of amazement. In that instant, the Cuban veteran, on the brightest stage, reminded the world that mountain intelligence could defeat brute force. It was his only All-Star Game. A perfect moment.

The unbreakable resilience on the mound

His moment of peak physicality came in 1963, not in a playoff game (the A's rarely saw them), but on a June afternoon at Kansas City's Municipal Stadium. Against the Detroit Tigers, Seguí became a titan. Inning after inning, as batters slumped to the bench, he was still there, defying the physics of the human arm. Eighteen innings. Two hundred sixty-three pitched. Seven hits, three runs (two earned). He lost 3-2 in the 18th, when fatigue finally took its toll on his control. But that silent feat—a record of endurance in an era that was already beginning to forget complete pitches—encapsulated his essence: a fierce pride, a disdain for pain, the conviction that his arm was a duty rather than a gift. That year, he led the American League in Complete Games (18) and Saves (20), a strange duality that foreshadowed his constant reinvention.

King of the Caribbean Winter

Seguí's true coronation did not occur under the lights of the Major Leagues, but under the warm tropical sun of Venezuela. For the fans of the Leones del Caracas, Diego was a deity. In the 1964-65 season, he wrote an epic poem: 12 wins, 0 losses, 1.26 ERA. It wasn't just ERA; it was absolute dominance. He pitched with a ferocity and a connection with the fans that he rarely displayed in the U.S. In Venezuela, he wasn't the exile, nor the nomad; he was El León, the hero who gave his all with every pitch. The stadium was his adopted home, the roar of the stands his anthem. His legacy there is deeper than any MLB statistic: it is love, respect, and the legend of the Cuban who became Venezuelan by right of dedication.